Friday, December 29, 2006

Peace?

After getting back from

“It is very bad,” Malik replied shaking his head. “Both hotels, empty,” he finished, using a sweeping hand gesture to emphasize the word “empty.” Dan and I nodded our heads in sympathetic concern.

“The travel advisories, nobody is coming,” Malik continued. “People are canceling trips.”

“Yes,” Dan replied, “This should be the high season. This place should be full of French tourists running around in orange pants and tank tops on winter vacation.”

“I know I know,” Malik replied despondently. “And what does this President do? He goes and builds an international airport in Hambantota District,” he finished with disgust.

“Really!” Dan replied, astounded, “That’s his home district isn’t it?”

“Yes,” confirmed Malik, “and he wants to make it a major port down there also.”

“Simple clansmanship, that’s all that is,” I remarked. “Does it make sense to have a major airport in that area anyway?” I asked, never having heard of Hambantota before.

“No,” Malik replied decisively. “There is nothing there. He wants the airport where there is already a small airport, very near Yala and that is all.”

“It’s really not the best place for an airport to provide access to the south,” Dan explained. “It’s near the Yala park, but it’s not even that close to the beaches, it’s too far east.”

“That’s crazy,” I replied.

“Meanwhile there are no tourists at all because of this war,” Malik added.

“Do you think that either the government or the LTTE wants peace?” I asked Malik.

“No,” He replied immediately. “They do not want peace,” he replied, frowning.

After Dan and Malik discussed past government scandals that were hard for me to follow, we said our goodbyes and headed home. Walking up the final hill to our house we passed another hotel owner standing on the balcony of his hotel. “Hello Tony,” Dan greeted him. “What do you think of the new airport?” he asked. Tony was a short Muslim man who always looked very dissatisfied. When he heard Dan’s question about the airport his facial features contracted into a level of disgust I had not yet witnessed in him.

“This is crazy,” he started, narrowing his eyes. “This airport in Hambantota. If there should be a new international airport then it should be here, in

“That’s a good point,” I replied, I had not thought of it before.

“Yes, the airport should be here,” Tony repeated.

“How is business?” Dan asked.

“Terrible,” Tony answered, pursing his lips. “but I am lucky,” he continued. I worked in

“That’s very good,” I confirmed. “The tourists will always come back to

“Yes, if they can ever find peace,” Tony replied.

“Do you think that the government really wants peace?” I asked. Tony paused for a few moments, “No,” he replied. “They do not,” he continued, wrinkling his nose and staring off toward the

When I googled the new airport I learned that it would be a 125 million dollar project slated for completion in 2009. The proposed site was a current bird sanctuary. While I was on the internet I decided to try and unravel a political cartoon I had seen the in the newspaper that weekend. The central image was a wounded tiger in a hospital bed with his arm in a sling. The acronym “LTTE” was drawn in on the bandage across his forehead. A man stood next to the bed with his back to the viewer. He held a bouquet of flowers behind his back with the acronym “PTA” drawn on the wrapping of the flowers. The man was passing the flowers to the tiger who reached for them with his good arm. I googled “PTA

Once I read about the PTA I understood the cartoon. If the Rajapaksa government revived civil rights abuses against Tamil citizens, such actions would only fuel the LTTE’s mandate to defend the Tamil people. I knew from frequent visits to the Tamilnation.org site that the LTTE styles itself as the sole representative of the Tamil people, and they seek to secure a safe homeland for the Tamil people. Tamils would then see the LTTE as a form of protection. Additionally, if

After reading through internet pages for most of the afternoon I turned to Dan at his computer across the room behind me and said, “I’ve got it, that PTA thing is the Prevention of Terrorist Act, now I get that cartoon we saw in the paper.”

“Oh yeah, I remember that,” he replied. “When I was here as an undergrad in 1997 there was a Tamil girl raised in

Thursday, December 21, 2006

Mehendi

My treat for coming down to

Once I arrived in

After lunch we set off in the taxi, not knowing if we were looking for a house, a store, upstairs or downstairs. Once we knew we were close the driver pulled over to ask a local man walking down the street. One quirk of the Sinhala is that they will never admit that they don’t know where a place is. Rather than admit ignorance, they will simply direct you elsewhere. Despite the fact that this man was literally standing in the street where we had to turn, just feet away from our eventual final destination, he pointed us back down the main road. Our driver insisted on carrying on back down the street until Dan convinced him to go back to the side road. Then he went on foot down the side road about 20 feet until he found the correct address.

I got out of the car in front of a very new, very modern house. I figured this must be it, so I rang the doorbell. An older, plump woman in a salwar and wearing the Muslim hijab answered the door. I nervously told her that I was here for mehendi. She smiled and invited Dan and I into the house. “Farhath will be down in a minute,” she explained in excellent English and asked us to sit on a bench in the hallway. The house had many levels, all semi-open and capped by a single high ceiling with ceiling fans. Looking at the polished granite floor and large lattice-work windows I realized that we had stumbled into the Muslim upper class of

Farhath herself came down the stairs from the bedroom a few moments later wearing a cream colored intricately embroidered salwar and matching hijab. “I’m sorry to make you wait, I had to feed my baby,” she explained smiling. Her English sounded very natural and she had only the slightest trace of a British accent.

Dan and I followed her up another set of stairs to a loft area across the great gulf of the downstairs from the bedroom area. I knew that mehendi could take awhile, so Dan had brought his computer. Farhath set him up at table in the loft area and we sat down on a couch. “So, what do you want?” she asked sitting next to me.

“The tops of my hands and arms,” I replied.

“Ok,” she replied, snipping the tip off her henna dispenser. The henna was pre-packaged in something that resembled the sort of thing bakers use to make decorative flowers on cakes. She grasped my left forearm in her left hand and immediately started drawing on my skin in long, elegant lines. Slowly shapes evolved out of the lines. “I went to

“Wow,” I replied. “I bought my own box at the market back home in

“I have been married just over a year, I have a baby, and I am only 21,” she remarked, looking up at me quickly and smiling. “That is very different than

“Well, actually,” I replied, “my parents got married at 19 and had me when they were 20, but that’s not the norm, no,” I agreed. I felt very relaxed talking to Farhath. I felt that I could talk at my normal speed and utilize my full vocabulary without having to simplify all of my thoughts and language.

“Are you married?” she asked, nodding to Dan.

“No,” I replied. “But I’ve been married,” I furthered with a gleam in my eye, feeling that if she wanted to know about American culture I would tell her. “I was married for almost five years. I got married when I was just a little older than you, I was 22. That’s not the norm in

“Yes, it is hard to keep a marriage together,” she agreed, nodding with an understanding that surprised me.

“Do you think you will marry him?” Farhath asked, nodding to Dan again.

“Yes,” I replied, “but we don’t have any sort of formal plans or anything.” We both paused for a moment and looked at Dan across the room, he was facing us but had his headphones on and was engrossed in his computer.

“Do you want to have children?” she asked as she moved down to my left hand, starting with bands just under my fingernails.

“Yes,” I replied. “I’m 28 so I have a little time before I’m too old,” I replied jovially. “But I need to wait until I am really in the right place for it,” I furthered seriously. “I am not one of these people that can just jump into it. I’m a nurse so it would be easy for me to work part-time, that’s what I would want to do.”

“Yes, I like being home,” she agreed. “This is the first time I have done mehendi since giving birth actually, it feels nice to be creative again” she remarked, stopping briefly to admire her work. “I love drawing on your skin, it’s so white,” she commented.

Farhath was quiet while doing some detailed work on my fingers. “You know, my marriage was arranged,” she told me.

“Really,” I said, surprised. “Did you parents place an ad in the Sunday Times?” I asked.

“No, my husband’s father works with my father” she replied laughing, “That’s funny that you know about those ads.”

“Are you kidding?” I replied. “I love the marriage ads. I read them every week. The whole idea fascinates me. How many times did you get to meet your husband?”

“We met at our engagement party, here, I will show you pictures,” She replied. She yelled something to her mother in Tamil.

“No kidding,” I remarked.

“Yes, but it was my choice,” she explained. My left hand was finished and she started on my right forearm in a totally different pattern of sweeping lines. “This house was my bride-gift,” she remarked.

“It’s beautiful,” I replied sincerely. “I totally love the floor. I have one of those red wax floors at home that turn your feet red.”

“Those are terrible,” she agreed, wrinkling up her nose.

Farhath’s mother came upstairs with the wedding album, a professionally produced book of glossy, bound, full-plate pictures. I flipped the pages carefully with my left hand as Farhath worked on my right arm. In one of the first pictures Farhath and her fiancé stood side by side, he wore a long, embroidered tunic and a red turban. She wore a saree with a long-sleeved shirt underneath tucked into the petticoat and a matching fashionable hijab. The couple posed happily as though they had known each other for years “Your jewelry is amazing,” I commented on the long 22k gold and ruby earrings and matching necklace.

“Oh, that’s just my engagement jewelry,” she replied. “I went to

“Can you ever wear all that jewelry again?” I asked.

“No,” she replied. “It is strange,” she admitted. “If I try to have less, then the old people, my grandparents and his grandparents will say that it is not enough. They will say that it is not a real wedding.”

“What about your daughter, can you save it for her?”

“No,” Farhath said laughing, “She will not want it. By the time she gets married it will all be old-fashioned.”

I turned the page to see her wedding saree and jewelry. Instead of the usual hijab she wore a gold head-wrap that looked like a more elegant version of turning your head over, twisting a towel around your hair, then standing up and flipping the towel back. “Your head-covering is really cool,” I remarked.

“Thank you,” she replied. “I had a designer make that for me. I wanted to cover my hair, but I wanted something different.”

“Ok, so these are pictures from the reception, but what happens with the ceremony?” I asked. I could tell that all of the pictures were from some local high-end hotel.

“Oh, I don’t go to the ceremony,” she replied. “All of the men go to the mosque. My father represents me. My husband, he is there, and his father. Then everyone else is there as witnesses. The more witnesses the better you know?”

“Right, right,” I agreed. “To make everything stronger.”

“Exactly,” she replied, nodding in approval and moving down to my right fingers. I was amazed at how different my two arms had turned out. Farhath continued to draw the henna on confidently, rarely stopping or re-touching.

“Then my father gives me to my husband and they speak their vows in front of everyone. Then there is the party at the hotel,” she said excitedly.

“So the ladies just show up for the party huh?” I asked teasingly.

“Yes that’s it!” she replied, “It’s really very nice,” she remarked as she drew the last lines on my fingers. There was no possible skin left to which to draw and I sensed that we both felt sad it was over. “I’ll go and get some lemon-sugar water to help bind the henna to your skin until you wash it off tonight,” Farhath told me a bit sadly as she went back down the stairs to her kitchen. In the heat of

Tuesday, December 19, 2006

New Intro

My Dad suggested that I write a better intro for the whole epic, so here goes:

Just before walking into the Charlottesville Target on a Sunday morning to buy Pepto-Bismol and sunscreen in mass quantities, my boyfriend Dan stopped me on the sidewalk just outside of the automatic doors and turned to face me. “Look, everyone goes through three phases of culture shock,” he explained. “First there’s the enchantment phase where everything is strange and wonderful. Then the anger and disillusionment phase where you can’t get anything done the way you want. If you persevere through the anger and disillusionment, you might make it to acceptance and live a productive life in the host culture. I’m going to do my best to help you in each phase any way I can,” he solemnly promised me, kissing my hand.

“Well, at least I have enchantment to look forward to,” I remarked sarcastically, entering the over-air-conditioned store from the warm summer air. A massive shiver shook my entire body and goose-bumps spread over my exposed arms. I grabbed a cart and headed toward the medical supply aisle.

“You know,” Dan remarked, “Serendib is the old Arab trader name for

“Hmm, that’s interesting,” I replied as I studied the various types of Band-Aids available, trying to find the right combination package.

“People say that it’s the island of unsought rewards from accidental discoveries,” he told me.

“You know, I remember looking at a big coffee table book of photographs of World Heritage sites a few years ago,” I replied, moving out of the medical supply aisle heading for the cosmetics. “I came to a picture of

“That was probably Sigiriya,” Dan replied, “and we can go see it easily. It’s a short day’s drive from where we’ll be living in

“It’s still just so strange,” I continued, “Sri Lanka has always seemed like a no-go to me, even though I have been to these places where terrorist groups actively target tourists and tourist attractions, like in Egypt, or the PKK in Turkey or the Shining Path in Peru.”

“The LTTE has sought to hinder the tourist trade, but it has never attacked tourists,” Dan explained. “The LTTE is funded by a large ex-pat community that is still seeking international validity. They don’t want to be seen as a terrorist organization, they want to be seen as a minority separatist organization fighting for a homeland, so they leave the tourists alone. Just don’t walk next to the Army Commander or a prominent Tamil politician and you’ll be fine,” he joked.

“Since you’re research is on Buddhist belief and ritual in the army, don’t you sometimes stand next to the Army Commander?” I asked concerned.

“Not very often,” Dan replied smiling.

“So you’ve been going to

“Right, starting with the undergrad semester in

“Ok, so, how close have you come? I mean how close have you been to the so-called ethnic conflict?” I asked

“Well, one time when I was a Fulbrighter I was in an area of

“I’m sure it’ll be fine,” I agreed. “I’m sure I am much more likely to get hit by bus or something much more mundane,” I joked.

“Right!” Dan agreed. “You are much, much more likely to get hit by a bus,” he laughed.

“Seriously though, things are starting to go bad in

“As long as the fighting was contained,” Dan replied. “As long there is not wide-scale civil unrest.” I nodded my head in agreement and started off to find flip-slops.

Monday, December 18, 2006

Social Economic Development

“This time we’ll go to

“

“

“I’m ready for another world,” I agreed grimly.

Mrs. Ratnavale’s house was another world as promised. From the outside it looked like an ugly circa 1970’s concrete block-style construction with strange plantation-shutter style oblong windows. Once inside however, my bare feet were greeted by meticulously clean polished dark burgundy floors. The slanted-open windows filtered in plenty of tropical sunlight and air, but the house remained cool and well-ventilated even without air-conditioning. Blue-patterned Chinese vases rested on well-made vintage wooden furniture and framed quality batik hung on the walls. An entire extended family of servants cooked, cleaned, and maintained the large house and small garden. As the servants ferried our bags upstairs they insisted I sign in the guestbook. Each resident put their name and organization or university. I signed Dan in as a Fulbright-Hayes from the

After briefly arranging our room we came back downstairs to see the small garden at the back of the house. The walls of other homes formed two of the garden walls and the house flowed into the garden in an L-shaped verandah on the other two sides. I found this postage-stamp sized little slice of manicured order stunning. A slim, young, Caucasian woman with dark hair sat reading in one of the chairs. As we walked along the verandah toward the woman in the chair another slender, older, Sinhala woman came out of the house near the seated woman. I recognized the walking woman as Mrs. Ratnavale from framed photos I had seen upstairs. She waved a socially well-polished “hello,” to Dan who returned her greeting, and then turned to the seated woman and said, “How are you feeling today?” She asked in a tone that implied a serious illness rather than a casual greeting.

“Oh, I feel fine today,” The seated woman replied and smiled up at Mrs. Ratnavale. Mrs. Ratnavale seemed satisfied with this answer and glided back into the house.

Worn out from the journey and intrigued by the reading woman who perhaps harbored some sort of interesting tropical illness, I sat down in one of the verandah chairs near her. I made sure to arrange myself so that my body was open to the woman reading the book. “How long have you been staying here?” I asked Dan once he had seated himself next to me.

“I’ve been coming here just about as long as she has been renting rooms,” he replied. “You see,” he continued, “She was widowed early and I think she started this business to keep her house,” Dan explained.

“It’s really nice,” I commented. “It’s a pretty interesting look into the world of

“I knew you’d like it,” Dan replied happily.

“Excuse me,” the seated woman addressed Dan in an American accent, “What organization are you with?”

“I am a Fulbright-Hayes scholar,” he replied. “That’s a senior Fulbright,” he clarified. Dan didn’t like to be thought of as just a regular Fulbrighter, a group he considered to be sporting dreads and doing their projects on “Post-Colonial Queries of Sri Lankan Beach Culture.”

“I see,” she mused, “and where are you based?”

“

“And where are you based?” I piped up.

“Trinco,” she replied, and I was elated. Here in front of me was a woman possessing not only a possible tropical disease, but also from Trinco. Trincomalee was on the northeast coast about 110 miles from

“Wow,” Dan and I replied in awe. We both knew Trinco was it, the true war zone in our own backyard.

“So, I mean, what’s it like up there?” I asked.

“Well,” she replied slowly, “I have very little freedom; an armed guard goes with me everywhere. Nobody goes out at night. I can see and hear some of the fighting, especially at night.”

“What projects does your NGO focus on?” I asked.

“We do social economic development, you know, small-scale infrastructure rehabilitation, livelihoods restoration, stuff like that” she replied matter-of-factly and paused. When met with our blank, uncomprehending stares she explained, “Basically we pay day-laborers to repair the roads after the fighting moves through.”

“Shouldn’t the government do that?” I blurted out. “I mean, shouldn’t they be responsible for the mess they’ve made?”

“Well…” she shrugged.

“So,” I began. “Let me see if I have this right. The government can trash Trinco and they know that an NGO will come along to pay their citizens to pick up the pieces so they can roll through the town again?”

“I signed up for a year assignment on this project, but I’m trying to get out early,” she admitted. “It does feel a bit enabling. I question what we are really accomplishing here.” I could see her total exasperation in this admission.

“Do you think that either side really wants peace?” I asked. She paused for a moment.

“No,” she replied. “The government clearly allows things to go on. Five telecom workers were abducted from their building by the LTTE and nobody saw anything. That big arms bust up there, how did all those guns get as far as they did? How then did they find them when they did?” We all sat in silence for a moment, thinking about the gravity of these issues.

“So, where else have you worked?” Dan asked, changing the tack of the conversation. As she began to list places I realized that working NGOs was a career path, an international corporate ladder. I felt stupid and naïve for ever thinking it was anything different. I envisioned most NGO workers more like Christine and Karen, people wanting to take a few months out of their live to live abroad and change the world. This woman was making a lifetime of aid work. She mentioned that after her experience in Sri Lanka she wanted to stay in the states for awhile and get her masters in International Development. “Then I’ll be able to get the really big jobs,” she explained.

“Ok,” I replied jovially, “but at what point do you get to ride around in the UN car with tinted windows and the snorkel on the front? Is that only for people with advanced degrees in Third World Hell Hole?”

“Probably,” she replied laughing.

“So, do you know Cindy?” Dan asked. As Dan and the NGO worker started to triangulate acquaintances, I studied her closely. She did not shift her weight or move around much in her verandah chair, which to me indicated some sort of exhaustion. Once they had established that Dan vaguely knew her roommate, an expat woman with seven indoor cats and a bread machine, I asked “So, I heard Mrs. Ratnavale ask how you were feeling, are you ill?”

“I came down to be tested for Typhoid,” she replied.

“Don’t you get vaccinated for that?” I asked, surprised.

“My vaccine is getting old, and just because you are vaccinated doesn’t mean that you can’t get it,” she reminded me.

“That’s one of those fecal-oral diseases right?” I asked. “Not too surprising considering that this is a culture where everyone eats curry and rice with their hands and there is rarely soap in the bathroom. How do they diagnose Typhoid anyway?”

“It’s a blood test,” she replied. “Then I have to wait a few days for results. It’s nice to get out of Trinco for a little while anyway.”

“I bet,” Dan replied, starting to stand up. “Well, we’ve got to get going to lunch; it was nice talking to you.”

“Good luck in your research,” she replied.

“I hope you feel better and they find a replacement for you soon,” I told her as I got up to leave. She brought her book up to eye level as we started off back into the house to call a cab.

“Man, Trinco,” I remarked to Dan once we were in the cab. “What was it like when you were up there?”

“I only got to go twice in the ten years I have been coming here,” He explained. “In 2000 some friends tried to get me to go. They assured me that the road to Trinco was ‘swept for mines every day.’” Dan laughed. “I wasn’t really comforted by that, so it wasn’t until the 2004 ceasefire that I finally went. First just to see it, there was so much hope during that time; this was right before the tsunami. They re-opened all of the roads. I went up there and Trinco was beautiful: beautiful white beaches, great diving and snorkeling. It has a great old Dutch fort also. It had so much potential. The second time was in 2005, after the tsunami. I went to interview a monk up there. Things actually looked pretty much the same; the hotel where I stayed was totally rebuilt. There were more NGOs and more relocation tents, that was about it.”

“It’s all just really sad,” I agreed. “I don’t think that either side really wants peace either, otherwise why would they have destroyed it? What is the LTTE fighting for at this point? They don’t represent most of the Tamil people, like the owner of the hotel down the hill. He’s a Tamil just running business, does the LTTE represent him? No. Do they represent the tea plantation workers? No.”

“Right,” Dan agreed. “And what you have to understand is that the LTTE is claiming a huge chunk of the eastern side of the island. A much larger area than they’ve ever been able to control.”

“Yeah,” I replied. “And then you’ve got these NGOs up there literally paving the way for them to fight back and forth in Trinco. No wonder that woman is questioning what can really be done here.”

“No kidding,” Dan replied, nodding in agreement.

Wednesday, December 13, 2006

Temple of the Tooth

I hadn’t been on foot in

Intending to be a tourist at least for the morning, I walked down the hill and around the edge of the lake along the white, rounded, parapet retaining wall with its filigree cut-out holes used for small oil lamps during pre-electric Christmas light festival times. This style of wall is meant to evoke rolling clouds and is found marking the perimeter of most temples in

I made my way to the throng at the shoe coral, one man was taking shoes and giving back little cardboard numbers and returning shoes all at once, servicing about 15 people at a time. I noticed that he would basically hand anyone any shoe they indicated and the cardboard tag system didn’t seemed correlated to shelf organization or anything else. Once barefoot I negotiated the grimy paved lot to the entrance to the

At the steps of the entrance gate I waited in a herd for a pat-down and to have my bag searched. In other countries this would have been a line, but here in

I followed the women around the corner to the next pat-down area. As I was about to get in line behind the royal-blue patterned woman, a tout stepped directly in my path, “come over to here,” he said, indicating the neighboring devali shrine by a courtly gesture with his right hand, “open time now,” he finished with a smile on his face. I looked directly at him, stunned that he had stepped to me in this fashion. He was tall, well-dressed, and younger than the average tout. He clearly thought himself as handsome and genteel. Wordlessly I turned into the pat-down booth. “Oh! So proud!” I hear him yell at me as the police woman ran her hands over my body.

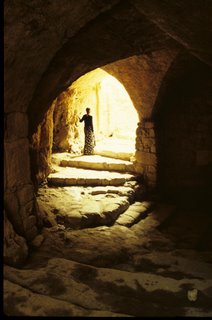

After the second pat-down we all started up the steps to the temple, across a moat, to the right, up some more steps, into a tunnel, and I started to get nervous that perhaps I should have bought a ticket some place way back before the shoe-drop. When we came out of the tunnel we took a left up some more steps and then at the entrance to the inner courtyard I saw the ticket booth. An old man pointed to the price list and tried to recruit me saying “wouldn’t you like someone to show the temple to you, to explain?” His approach was different; he was straightforward in offering services, not trying to drag me off someplace else. I remembered the official guides I had used in

I had arrived in time for the morning puja, or offering, at

Two drummers and a clarinet player were already in full swing on the ground floor in front of the two-storey free-standing inner shrine building, but nobody seemed inclined to stop and watch. I spotted the older woman in the tan-patterned saree and followed her up a set of stairs. At the top of the stairs was a long hall running the length of the building with the upper floor of the inner shrine building as its focus. Devotees sat four deep along the back wall of the balcony facing the top floor of the inner shrine building. Some people prayed with their hands in prayer at their hearts or on top of their heads, others chanted to themselves, and a few stared off into space. There was a long table for flower offerings in front of the entrance to the inner shrine area, lotus, sal, and jasmine flowers were already pile up a foot high on the table. I looked at the pretty flowers and thought that I would much rather take them home and put them in water than leave them in a heap, “But that’s probably the point,” I decided.

I had never encountered a religious structure with this set-up. On my first trip to

I knew from skimming academic sources that a very scripted and elaborate ritual was taking place behind the closed doors. The monks first made themselves ritually pure and then offered curries, rice, sweets, water, a toothpick, cloth, a fan, a yak tail, a bell, camphor, fragrant scent, and flowers to the relic first at dawn and again before lunch. Rather than wash the reliquary itself, the monks act out ritual cleaning of the face and body of the Buddha. Dan has observed the preparation of the meal and told me that they also sometimes make smoothies for the relic. The relic, like the Buddha and the monks, does not eat after

Hindu ceremonies mostly take place in great secrecy also, but the lay participants get the blessed food to consume to feel a greater connection with their god. Looking around at the other people on the floor I wondered how this ceremony affected them spiritually. There wasn’t much to see and no sermon being preached to stimulate their minds. I knew it was over when the drumming stopped and people started to drift away. I followed the old woman down another set up steps and into the octagonal library room with a monk reading a palm leaf manuscript at a desk along one wall and a gold-tone Buddha statue in the middle. Still trailing the old woman I followed her in another small shrine room with statues of the Buddha and his two main disciples behind a wall of glass.

On my way out of the temple I stopped by the Raja Tusker museum where the last great elephant to bear the tooth relic in the Perahera parade is taxidermied. I found Raja in a small out building behind a glass wall with photos documenting his life along the walls.

Raja stands 12 feet at the shoulder and carried the relic for 50 years before his death in 1988. The temple is has been unable to replace Raja since the ideal elephant would have some unusual characteristics, including a flat back and a tail that touches the ground. Since temple elephants must be celibate, his DNA has been lost. After a peek at Raja, I headed back down the long walk and lawn leading to the temple and exited the compound to the side far away from my shoes. I walked with my barefeet past the stalls selling flowers, clay lamps, and oils for offerings, like a parking lot pilgrim.