6th Infantry Camp and Mihintale Part 2

It was 2:30 by the time we reached the entrance to the 6th SLLI camp. The soldiers on guard lifted the barricade immediately upon seeing the red Lancer, no questions needed. We drove straight through the small camp to the Officer’s Mess. Captain Keerthi was the only officer at the camp. He lived in one of the rooms off the small mess hall. I had seen pictures of Keerthi, but I was not prepared for his energetic demeanor. In his black Army T-shirt and camo pants, he seemed to always be in motion, shaking Dan’s hand, shaking my hand, shaking Thilak’s hand, ushering us into the mess hall, asking us to sit, gesturing for sesame cakes and ginger beer to be brought. Even when seated he was always shifting, moving, speaking, and gesturing. Dan translated snippets of the conversation for me. Keerthi relayed the success of his eggplant patch and the recent restoration on the tank bordering the camp. In the arid north country of Sri Lanka, huge earthen work reservoirs called tanks were constructed thousands of years ago. Rather than dig down to create the reservoir, the ancient local inhabitants built a series of forty foot embankments, each wide enough to drive a car down the top of, to flood entire plains. Most of the ancient tanks fell into disrepair when Anuradhapura was abandoned in 1017 in response to an invasion from the north. In the 19th century the British “rediscovered” the ruins and began restoration on some of the tanks. While the tanks were dry for hundred of years, Ironwood trees had grown in their beds. When the tanks were then restored to water-holding capacity whole forests had been flooded.

As Keerthi took us down the road towards the tank’s edge to point out a repaired section of the wall his soldiers had recently completed, Dan asked about some fresh ditches he saw on the sides of the road. Keerthi replied in English: “My friend Dan said if the roads in Sri Lanka were fixed, the troubles would go away. I do my part,” he finished, proudly gesturing to the new drainage ditches. Dan laughed. “On my camp,” Keerthi continued, “the roads will be fixed.”

“I can’t believe that you said that!” I admonished Dan, laughing.

“I must’ve had a bad trip up once,” he replied shaking his head and still laughing.

When we arrived at the edge of the tank the water was almost up to a small gazebo and two small resthouses. “Wow,” Dan said, “We used to be able to walk almost out to the middle,” he marveled. The embankment of the tank ran perpendicular to the marshy, gradual edge of the tank we now surveyed. I could see the fresh rocks plugging a large section of the embankment across the tank. Keerthi got out plastic chairs so we could all to sit in the gazebo on the water’s edge. I watched slender white herons regally stalk through the water, delicately picking at its surface as Dan, Thilak, and Keerthi talked in Sinhala. A strong breeze over the surface of the tank pushed up tiny little whitecaps just beyond the marshy area. In the middle of the tank the bleached branches of the dead Ironwood trees reached up like skeletal fingers. As I watched the water, one of the village people who worked on base walked down the water’s edge and proceeded to walk through the water near the gazebo to a trail starting on a small peninsula jutting into the water across the shallow marshy section. As the villager proceeded through the water up to her knees I realized that a trail of open water ran down the middle of the marsh grass and connected with the trail on the other side. The trail must have been used for many years as dry land when the water was still low. Now that the tank wall was fixed and the water rose, but the villagers still kept to the same path. Soon after the woman had crossed from the camp-side to the trail-side, two men crossed through the water from the trail to the camp. I wondered how long it would take the villagers to make a trail that looped around the marsh over to the camp or if they ever would.

After sitting for a spell at the gazebo, Keerthi hopped up and insisted that we go and see the eggplants. When I told him that eggplant curry was my favorite he broke into a big smile. We walked around the perimeter road of the camp to a large vegetable patch roughtly 100 by 100 meters. Keerthi vigorously checked each plant for fruit, harvesting all of the mature eggplants he could find for our dinner.

After the eggplants Dan and I unpacked in our resthouse room in the middle of camp, next to the rabbit pen. The rabbit pen was large and elaborate, about 20 feet in length and 10 feet in depth. A series of pipes and boxes with multiple entrances had been installed. The large brown and white rabbits hopped through all of the pipes and shelters at once, their movements permeating every corner of the pen. In the middle of the pen a huge pile of green alfalfa hay had been deposited in the morning. Our room was very basic, no hot water, no towels, no top sheets on the bed, only bottom sheets and pillow cases. It did however feature nice mosquito netting over the bed and a ceiling fan. We had brought towels but forgot sheets. “An important part of going on vacation was to make you miss and appreciate your home,” I commented to Dan. “I think this’ll do just the trick.”

“It’s not too bad though right?” he asked.

“Seriously, it doesn’t smell,” I agreed. “I’ve done much, much worse.”

After unloading our gear we set off with Keerthi to the local temple on the other end of the tank embankment from the camp. As we left the camp, Keerthi waved to the soldiers on duty at the gate. They replied by saluting and giving a ceremonial knee-lift-stomp gesture. We were quiet as Thilak drove the car down the embankment until Keerthi began singing what I could only guess was a Sri Lankan folk song. He continued singing until we pulled up in the parking lot.

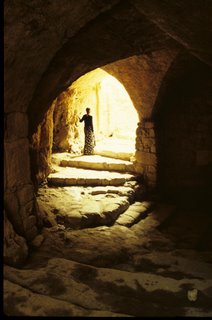

In the packed-dirt parking lot the foundation of an ancient temple was working its way up from repeated sweeping of the area. Thilak parked next to the temple foundations and we piled out. A quarter of Keerthi’s men were staying at the temple and doing restoration work on its grounds. I mirrored Dan, removing my shoes and following him up a short flight of steps to a large flat rock with a white seated Buddha statue on its summit. The large Buddha statue was about fifteen feet tall and beautifully rendered, eyes half-open and hands resting in the lap.

Dan and Thilak bowed to the monk of the temple while I nodded my head. The monk looked like he had not taken a razor to his head in two weeks. Dan had recorded several complaints about this monk and his teacher from the villagers. It was said that the monk’s teacher, the previous monk of the temple, had gotten a village girl pregnant and went to the local female medium to secure an abortion spell. One of the villagers also warned Dan that “if the [monk] teacher pisses standing up then the students will piss while walking.” I didn’t understand the expression until Dan explained that monks have to sit down to urinate. Standing on the rock in my barefeet I thought about this expression as I examined the monk’s head of hair. An Army Colonel Dan had met at Army Day came over to greet us. After I was introduced I left the group to walk to the edge of the rock and capture a few pictures of the huge stupa of Mihintale silhouetted by the sunset across the tank. I then sat on the rock and listened to my iPod until Dan approached me and told me it was time to go.

Instead of getting back into the car, the group retired to the monk’s office and living quarters for tea and cookies. Since monks can’t eat after noon, the monk had only the tea. I sat next to Dan, Keerthi sat across from me, the Colonel next to him, and the local chief of police joined the group, chatting with Thilak in the monk’s bedroom. Photographs of monks of the temple decorated the walls of the residence. The older studio photos depicted monks in dignified head-shots. The photo of the current monk was twice as large and taken on location at the temple, showing the monk with a cleanly shaven head, eyes closed, meditating on the rock near the Buddha statue. Looking around the room I felt far, far away from the suburbs of Richmond, Virginia, where I had grown up until I spotted some fake flowers with glue-gun droplets of water on them and realized that some things transcend all cultures. When tea was finished Dan made an appointment to interview the Colonel the next day and Keerthi sung in the car all the way back to camp.

After our cold showers we put the fan on, pulled the mosquito netting down, and bundled ourselves into our sarongs for sleep. “You know,” Dan started, “Thilak was staying here when the LTTE hit that convoy of soldiers going home on leave. That night the villagers all came to the base terrified, saying that there were men with guns in the woods. So Keerthi brought the men out and they found a few hunters.”

“No kidding,” I replied, raising an eyebrow in the dark.

“Yeah, Thilak had a scare that night,” Dan replied.

“I could see that,” I mumbled before falling asleep, exhausted.

The next morning Dan and I ran a few times around the perimeter of the base. We were waiting for breakfast when two soldiers, both in full uniforms, strode purposefully to the guinea pig hutch on stilts for a morning review of the animals. They stood for a few moments with their hands behind their backs seriously discussing the animals before moving on the officer’s mess. After breakfast Dan and Thilak went out to interview a gunner usually assigned to shoulder-launched rocket propelled grenades, or RPGs. The soldier was currently assigned to paint elaborate murals on a nearby temple. “I don’t like to waste rounds,” he told them. “I only like to shoot when I am sure I can kill someone.” When asked if shooting at the enemy was a sin he told them that life was good and bad actions both. While they were on the interview I went back to the gazebo with my books and iPod. After lunch they returned to the field and I returned to the gazebo, working on a survey of Hinduism.

All of our meals were served in the dinning room of the resthouse. Keerthi even gave special instructions to the camp cook to prepare a few bland vegetables to suit my American palate. After two days of interviews for Dan and days by the tank for me, we left on Friday afternoon for Kandy. When we went to say goodbye, Keerthi presented Dan with a bill for 23,000 Rupees, about 230 US dollars, explaining with a straight face that the new Army Commander had raised the rates before bursting into laughter. The total price for all three of us was actually 1,800 Rupees. After making plans for Dan and Thilak to return in February, we headed out in the Lancer back for the hills of Kandy.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home