Monday, July 23, 2007

Optional Ending

The Promised Land

We sailed through customs and our flight took off on time. We connected first through Dubai and then through JFK to reach Houston on schedule, where my mom and step-dad picked us up from the airport. I was an only child and my mom had me when she had just turned twenty, so now in my early adulthood she was still young and vigorous, working out four or five days a week in addition to her full time job in a doctor’s office. My step-dad, Byron, had never had children. At 6’4” with red hair and freckled skin he looked like a Viking.

“I know you guys are exhausted, “ my mom said when we had everything loaded into her Volvo wagon, but do you mind if we stop at Whole Foods on the way home?”

“That would be great,” I replied as I settled in against the immaculate beige leather backseat. As Byron drove back from George Bush International Airport through the intricately knotted elevated freeways of Houston I gazed out the window. “This is my birthright,” I thought with deep satisfaction, “These elevated roads with no potholes where travelers move quickly and safely. This is a great accomplishment of my people.”

“Sara, put your seatbelt on,” my mom reminded me from the front. “Ah, what is this seatbelt of which you speak?” I joked while pulling the shoulder harness down and clicking myself in. I immediately felt like the shoulder-strap was choking me so I put it behind me and kept the lap-belt around my waist. “I guess some things are going to take a little getting used to again,” I mused.

Once in the Whole Foods my mom just wanted to pick up a few things and Dan was tired, but I began to wander through the mountains of fruit and started touching all of the neatly displayed oils, lip-balms, and lotions. I was still caressing a bar of soap when my mom finished checking out. “Come on Sara!” she called out from the nearby express lane. “Dan’s about to fall asleep on the bench next to the store managers office.” Reluctantly I replaced the soap and followed my mom out of the store and back into the car, purposely not fastening my seatbelt. As we pulled out of the parking lot I noticed a mosquito buzzing near my arm. “Go ahead and try it,” I thought to myself. When the mosquito landed I killed it easily.

While my mom fixed dinner I offered to take, Emma, her yellow lab out. I planned on staying in and around her yard, so I didn’t bother to wear any shoes. Walking through the grass in the late afternoon reminded me of my childhood summers roaming the fields of Wisconsin until I noticed a few black ants biting my foot. I brushed them off and the area continued to sting for a few minutes and then went away without even leaving a red mark. “These bugs are pathetic,” I thought to myself with disdain while watching the dog sniff the base of a tree. I remembered when an ant bit my little toe when I had my shoes off at a rural temple back in Sri Lanka. The pain had been excruciating and the toe turned red, swelling up like a little smoky sausage overnight. The skin at the nucleus of the bite split and oozed for days while I hobbled around. “Now that was a bug-bite,” I recalled to myself as I headed in with the dog.

My mom served slices of baguette on the table with prime rib and the rosemary roasted potatoes she had prepared for dinner, leaving the other half of the baguette out on the countertop. Throughout the meal I found myself anxiously watching the bread, expecting it to be colonized by ants at any moment. “Man,” I remarked to Dan, Byron, and my mom, “These American bugs are sleepy and slow. If I left bread out like that back in Sri Lanka it would already be covered in ants. I just got bit by some ants when I took the dog out and my foot is totally fine.”

“Really?” my mom asked. “The bugs were that bad?”

“Yes,” Dan chimed in, “They’d invade anything, even your computer, and you had to zip-lock bag any open food like bread or cereal.”

“What happened when they invaded your computer?” Byron asked.

“Well,” I began, “we went away for a few days and I turned my computer off. When we got back home I turned it on again and ants fled through the ventilation holes. After that it started to run hotter and hotter and slower and slower. It started to get glitchy and started crashing, so I backed everything up and took everything off of it I could. I would only have one application open at a time, but finally it wouldn’t boot anymore when you turned it on. It just went to the blue screen of death,” I finished sadly.

“So what’d you do then?” Byron asked.

“I took out the hard-drive and physically destroyed it and then gave it to a friend, I mean, maybe someone could get some use out of it somehow” Dan replied.

“Sure, sure,” Byron replied.

“So what do you think you’ll miss?” my mom asked. Dan and I were both quiet for a moment, chewing our steaks thoughtfully. “There must be something,” she prompted.

“I’ll miss the Galle Face, that great colonial hotel I sent you the link for,” I answered.

“I remember, that place looked really pretty,” my mom replied approvingly. “What about you Dan?”

“I’ll miss,” he started and paused, “Can’t say the Galle Face, that one’s already taken,” he paused again. “I guess there is some food I’ll miss that you can’t get here,” he replied unconvincingly.

“Like what?” my mom asked.

“Jackfruit,” Dan replied.

“What’s that?” she asked, perplexed.

“It’s a big fruit,” Dan explained. “When it’s young it can be prepared like meat. When it’s older it gets sweet.”

“Hmmm…” my mom replied.

“When they get older they are big too,” I added. “Up to 40 kilos, about 80 pounds.”

“Did you guys ever make it to the beach?” Byron asked.

“No,” we replied in unison.

“Why not?” my mom asked, “I bet the beach was really nice.”

“It’s not like here,” I explained. “You can’t just throw the dog in the Volvo and drive to Galveston. Either you take the local train, which is a total nightmare, take the bus, or hire a car for forty-bucks a day. Then when you get to the beach you have to spend some money to stay someplace nice, so it’s not like a cheap little vacation if you want to do it in any degree of comfort,” I finished.

“I thought you had a car there Dan?” Byron asked.

“I sold it to my research assistant,” Dan replied. “Plus, it’s really stressful for me to drive.”

“But the place is an island, how far away can the beach be?” Byron prodded.

“As the crow flies, not to far,” I replied. “But you’re looking at a full day of transit from Kandy no matter how you do it.”

“Wow,” Byron replied, mocking us slightly. “Sounds like it was better to stay home.”

“That’s basically what we did,” I confirmed.

“OK! Who wants pecan pie?” my mom asked from the kitchen.

“So Sara, when are going back to work?” Byron asked as my mom was dishing up the pecan pie.

“The important first step is finding my scrubs in the basement,” I replied sarcastically. “Really though, I don’t know,” I admitted. “We need to get my car home and unpack. There’s plenty to do around Dan’s house since he’s basically been renting it out for the past four years.”

“I think that’s good,” Byron answered as the pie arrived. “I think you are going to need to take some time,” he warned me.

During our car trip back to Virginia we took a detour through Chicago to see my best friend from high school and attend her baby shower. My friend from high school, Kim, was six months pregnant with her first child. She and her husband both had jobs at law firms and lived in a beautiful apartment in Andersonville, a stylish neighborhood on Chicago’s north side near the lake. Kim and I had been best friends in high school, lived together in college, and visited each other frequently after college. We even got married around the same time. Sitting in her tastefully updated, well-appointed apartment listening to her describe the baby’s kicks I realized I was divorced, broke, unemployed, and homeless. “So, when are you guys going to get married?” Kim asked when the baby stopped kicking.

“Well, we weren’t going to do it in Sri Lanka now were we?” I replied as Dan squirmed next to me on the couch. “You should have a baby too,” she teasingly commanded and started to stroke her belly.

The baby shower was thrown by one of Kim’s friends from graduate school who also lived in a spectacular apartment and was radiantly pregnant herself. It occurred to me that these people were real adults living proper adult lives for people our age. “So Sara, what did you do in Sri Lanka?” Kim’s sister asked me next to the punch bowl.

“Well, I kept up with the house, lot’s of laundry, that sort of thing,” I began. “I mean, a house gets dirtier much faster in Sri Lanka because you have to have the windows open all the time,” I explained weakly.

“You didn’t do anything with nursing?” she asked, surprised.

“No, medicine is all, really different over there,” I explained.

“So then when are you going back to work?” she asked.

“I need to get home first,” I joked, got my punch, and moved into the living room where I spotted Kim’s mother-in-law, Nancy. “So Sara, how was Sri Lanka?” she asked.

“It was really something,” I remarked lightly, raising my eyebrows and quickly trying to divert the conversation to Kim’s sister-in-law’s pervious year of college. “So when are you and Dan getting married?” Nancy asked, “I really like him,” she confided.

“I really like him too,” I replied. “But even though we lived together well in Sri Lanka, that’s not real life in America and everything that comes along with it. I just have to see what that’s like first,” I explained. Nancy nodded her head. “That’s probably wise,” she confirmed as we moved back to the dining room to get some hors d’oeuvres. While I was munching on a little slice of gourmet pizza with goat cheese, basil, and fresh fig I met up with one of my friends from college. “It’s amazing that Kim’s pregnant,” she remarked.

“Yeah, it’s pretty crazy adult stuff,” I replied.

“Do you think you and Dan will have kids?” she asked.

“Well, Malaria can be dormant for six to twelve months,” I began, “So it’s probably better to wait that out,” I joked. I remembered the one time I called my mom and told her I had some interesting news. She thought I was pregnant but really I was calling to tell her that I had tested positive for exposure to Tuberculosis and was starting treatment.

“I don’t want to wait too long,” she answered. “Hey, where were you this past year again?” she asked.

“Sri Lanka,” I answered.

“So how was that?” she asked.

“Well, it was pretty much the way you’d expect a Third-World country with a quarter-century civil war to be,” I answered wryly.

“But aren’t they Buddhist?” she asked. “Shouldn’t they be, you know, non-violent?”

“No, the people relate to Buddhism just like people relate to any other religion, ” I explained. “They relate to the Buddhism they know culturally, the rituals, the festivals, and giving to the monks for merit. They don’t relate to the philosophy the way most Westerners do. That’s what I learned. Going in I thought because I was all into yoga and some Buddhist philosophical ideas I would feel some sort of resonance with the culture,” I added.

“Did you?” she asked.

“No” I answered simply. “Instead of learning more about the tradition I have come back feeling less interested in Buddhism, yoga, curry, and anything else that reminds me of the region,” I commented as the hostess called us into the living room for Kim and her husband Pete to open presents.

When we had cleared the loops and construction of Chicago and Dan was able to lock in the cruise control on the highway I blurted out, “If one more person asks me when I’m going back to work or when we are getting married, I don’t know what I’m going to do. I’m running out of pithy answers.”

“That’s just the normal stuff for people to ask,” Dan consoled me. “It’s really hard for people to really understand what we’ve been through because it’s so far outside of the range of their experience.”

“I feel old,” I replied.

“Living overseas does that to you,” Dan explained. “You come back and think ‘what’re all these crazy kids listening too?’ and you feel out of touch with technology and everything.”

“For me it’s that,” I agreed, “And the sense that everyone else’s life has gone on and developed. Lots of my friends traveled in college and their early twenties, and now they’ve settled down and I’m just wilder. Now they’re talking about layettes and I’m just glad I don’t have any new mosquito bites.”

“What’s a layette?” Dan asked.

“I didn’t know either,” I answered, “I had to look it up. It’s a set of clothing and bedding for a newborn.”

“Hmmm.” Dan replied.

“Before we left people would say ‘oh what a wonderful experience that will be,’” I continued. “But right now I just feel disoriented, overwhelmed, and my GI system is in ruins.”

“Look, I know you could go back to work this week if you wanted to,” Dan replied, “But I don’t want you to feel pressured. I want you to take some time. I am going to get reimbursed for all of my airfare from Fulbright and then the dissertation-writing grant will kick in soon. We’ll have plenty of money.”

“That’s good, I think that will be good,” I replied sincerely and started to scroll through the podcasts on the iPod to find some listening material.

For the weeks we spent in Houston and Chicago I felt on some level that we were just on vacation from Sri Lanka and we would be going back soon. It wasn’t until we got back to Dan’s and started to unpack that I started to feel that we were back for good. It was strange for me at first to see my flatware in the kitchen drawer and the dresser my grandfather made for me when I was a baby in the bedroom. It took us three weeks of steady work to combine households. I hung up my sarees next to my collection of vintage dresses in my closet and put away my scrubs and work clogs, wondering what sort of job I would find next. I brought up boxes of my own books and started putting them on the shelves, some for reference, some favorite reads, and some on the to-do list. Looking at my books I suddenly thought “This is who I am! I have books on tea, yoga, climbing, and travel.” I felt as though my own interests were a name I had been trying to remember for days that suddenly popped into my head as I pulled a coffee table book on Turkey out of a box. Sitting on the floor amongst empty boxes, still-packed boxes, and piles of my belongings I started to flip through the book on Turkey, savoring the pictures of my favorite mosques and focusing with interest on pictures of places I hadn’t visited. Dan was unpacking his own boxes of books in his office across the hallway. “I’ve got some reading material for you,” he remarked as he entered my office with two books in his hand. “They both detail the introduction and propagation of Buddhism in America,” he explained, handing them to me.

“Great!” I replied, putting down the picture-book of Turkey and starting to thumb through the chapters of the new books.

Once the house was unpacked we decided to go out to our favorite restaurant in Charlottesville, a Spanish tapas place called Mas to celebrate. “So what’s next?” I remarked to Dan as I looked through my sarees, trying to decided which one to wear.

“I guess we will schedule a curbside rubbish pick-up to get rid of that filing cabinet and some of the other stuff Salvation Army wouldn’t take,” he replied, pulling on his new cowboy boots from Houston.

“No, I mean travel-wise,” I clarified. “Are we going to go to India this winter for you to finish up some of the research you started on the Jains? I was thinking I can work full-time, pull in some overtime, then I could just quit again and we could go for a month and a half or something.”

“Are you crazy?” he asked, “How can you even think about that?” stopping in the middle of pulling on his second boot.

“But, don’t you want to go back to India?” I asked, surprised.

“I have to stay home and write, and go to the annual conference and try to get a job,” Dan replied, slightly stunned. “Then there’s my first year of teaching. That’s going to be really stressful,” he continued. “After that, maybe.”

“I guess I didn’t think about all that,” I admitted. “You think you’ll have to write all the time?” I asked tentatively.

“A dissertation is a pretty big project,” Dan assured me.

“Well, it sounds like I just have to take a trip to Turkey on my own then,” I replied, grinning. “I’ve always wanted to do a solo trip. For me that’s the final frontier,” I added thoughtfully.

“Will you send me a postcard?” Dan joked as I started to drape the saree and mentally outline the trip. The best time would be the early spring I decided. I knew could fly out to Van in the east and work my way back. That could probably be a two-week trip including a few days in Istanbul. “But if I had more time,” I ruminated to myself while pinning my saree, “I could go out through Ankara and go back along the Black Sea Coast in the north.”

Exodus

After our Northern Tour we had one week left in Kandy followed by two nights in Colombo. As Dan continued translation with Thilak I planned how to dissolve the household, piling yoga mats, canned food, and various utensils in the empty living room for the “free tag sale,” I had planned for the middle of the week. We had promised the blender to one friend, the water purification system to another, and the slingshot to someone else, so I arranged for everyone to come to the house two days before our departure to collect their loot. On the appointed day people came buy to collect their items and say goodbye. Delia, my friend from Goenka, came by just after lunch. After she selected the food she wanted and set the yoga mats aside we sat on the porch for tea. “What do you think you’re going to miss about this place?” I asked. She paused for a moment before replying. “The lush green,” she replied. “It’s green here all the time, the trees and bushes are always in bloom.”

“It is lush and green,” I conceded. “But I miss the seasons,” I countered.

“What do you think you’ll miss?” she asked.

“I have no idea,” I replied. “Really, I’ll have to get back to you on that once I get home,” I finished, shrugging.

“I’m about ready to go too,” she agreed.

“I hope you come and visit in the States,” I told her sincerely, with a pang of sadness that I was leaving and she would still be there.

“For sure,” she replied nodding. “I am thinking about the landscape architecture

Program at UVA, so I’ll want to come and check that out for sure,” she re-assured me as the doorbell rang and I rose to let in one of the scholars who lived down the street to get the blender.

At the end of the day Malik came and took everything leftover and bought our washing machine. He lingered in our empty dining room asking us about our travel plans and filling us in on his. “Tomorrow I am going to France, my wife and daughter, they are already there” he began, “Perhaps this time I will stay,” he remarked sadly.

“And leave all this?” I teased.

“This government is very bad,” he explained, “the tourists have not been coming, they are not coming,” he finished wearily. He seemed sad, almost defeating by the ongoing problems. We promised that when we returned to Kandy we would stay at one of his hotels and he smiled. “Yes, and if you come to France, email me. Come and stay with us,” he told us happily. “We will meet again,” he added as we walked him to the door and he headed up the steps to his van waiting at the road.

We spent the next day settling the phone bill and shipping boxes. To ship Dan’s three banker’s boxes worth of books we loaded them into Manju’s three-wheeler and headed down the hill to the Buddhist Publication Society, the Buddhist equivalent of a Christian bookstore. This “Christian bookstore” was the biggest bookstore in town and government subsidized, carrying a large selection of titles in both English and Sinhala as well as small selections in German, French, and Japanese. As Dan made the arrangements with the manager I perused titles in the English section such as “A Buddhist Response to Contemporary Dilemmas of Human Existence,” and “Buddhism and the God-idea,” then “The Smile of the Cloth and the Discourse on Effacement,” followed by “Transcendental Dependent Arising,” and “Matrceta’s Hymn to the Buddha.” I realized that I had no idea what most of these books were talking about. I felt incredibly ignorant of the tradition as the title “Maha Kaccana: Master of Doctrinal Exposition,” jumped out at me. “What the hell is that?” I worried and began to feel overwhelmed. I felt as though every title came straight at me completely unfiltered, I had no ability to judge what might be an insightful book and what was likely to be garbage. I had no ability to critically evaluate whatever the author said about Buddhism. Just like my experience at Goenka, whatever the writer suggested about Buddhism would become true for me. It struck me that in an actual Christian bookstore I would probably be able to at least understand the vast majority of the titles of the books and could probably pick out something that might interest me.

“Find anything you like?” Dan asked, coming up behind me.

“I was thinking of picking up a copy of ‘Self-Made Private Prison,’” I replied. “Do you think it’s a how-to guide?” I asked sarcastically.

“Take a look at ‘Buddha: The Super-Scientist of Peace,’” Dan replied, “That’s by your friend Goenka,” he finished as I rolled my eyes. “And what about Buddhism and Sex?” Dan joked, pointing to another title.

“Hmm…”and I replied, “Is that the embodiment of the rich history of Buddhist sexuality?” I asked laughing. “This stuff is all really overwhelming,” I continued, “Some of it is crap and some of it isn’t and I can’t tell the difference, except for ‘Buddhism and Sex’ that is. Even I can tell that’s weak.”

“If you want to read books on Buddhism,” Dan answered, “Don’t worry about these, most of these are translations of Sinhala texts, commentaries on Sinhala texts, and monks trying to tame a renunciant tradition and make it something palatable for mom and dad. It’s not the best way to really learn about Buddhism,” he explained as we left and got back in the three-wheeler.

On the way back up the hill I thought about how life in America would be different when we got back. “Would I want to go back to the yoga studio with all of the chanting in Sanskrit and pictures of Hindu gods everywhere?” I wondered. Yoga suddenly seemed too foreign, too much like Sri Lanka and the Buddhist Publication Society. I hadn’t done yoga at home since getting back from Goenka. Yoga seemed too much like Goenka, focusing on my breath, clearing my mind, and experiencing my inner world head-on. “When I get home I just want to run,” I commented to Dan as we walked back down the steps to our house. “I want to run and maybe lift weights but not even nautilus weights, I just want to pick up heavy objects. Just really simple stuff,” I finished.

“I’d like to join the gym too,” Dan agreed, opening the door. “And maybe I should start going to church,” I mused to myself as I changed from my outside shoes to my inside slippers.

I had heard the term “reverse culture shock,” but I didn’t really know what it meant before. I had never thought of my return to the States as anything other than indulgence in my favorite restaurants and having my car back. Sitting down at my computer after the trip to the Buddhist Publication Society and looking up the worship schedule at the local Unitarian Church, I suddenly realized that returning to Charlottesville was not going to be all unpacking my favorite clothes and kissing the floor at Target. I remembered one of Dan’s professors telling me that after he came back from a year in India as an undergrad he just had to party really hard in New York, just to see if I existed. I could understand that now. I could see how he would be driven to root himself back into his home culture. “Of course I’m going to be different, that makes sense,” I reminded myself. I had just assumed that I would be different in some sort of wise, more serene way, not different in a burned-out and alienated way.

On May 12th, 2007, the hired van pulled up in front of the house. We put our two big backpacks and our two roller bags in the back, put our carry-on bags in the front, and pulled away from 65 Rajapihilla Mawatha. As we drove down the hill and along the lake I concentrated on the scenery, memorizing the curve of the lake, the tree full of huge bats, the white, rolling, parapet wall meant to evoke clouds. “I can’t believe we are really leaving,” Dan remarked. “I can,” I answered definitively. “I feel like I have been here forever. Seriously. I can remember sitting on the porch and thinking ‘when is this going to end?’” I joked. Dan chuckled, we pulled out our respective iPods, and settled in for the three hour journey to the Galle Face Hotel.

“Now here’s something I’ll miss,” I commented as the doorman opened the heavy teak door for us to enter the cream-colored Regency lobby. The porters immediately began attacking the heavy luggage. I indicated which bag should be brought to the room and explained that the other three should be stored for the next two nights as Dan went to the reception desk. While Dan checked in I sank down into one of the olive-colored raw silk couches and watched the sun sparkle on the Gulf of Mannar through the glass. “You’re not going to believe this,” Dan said coming up behind me. “They upgraded us to a suite.”

“No shit,” I replied, stupefied. “I love this place.”

“This is a great hotel,” Dan agreed, helping me up out of the soft couch. “And it is one of the few places that doesn’t have different local and foreign rates. They charge everyone the same and it seems that they reward their frequent customers,” he continued as we followed the porter with our bag towards the polished copper door of the elevator.

The Ocean Suite occupied the half of the south wing of the hotel with a straight-on ocean view along the back wall and a view of the sea as well as into the courtyard, the north wing of the hotel, and up the Galle Face Green on the sidewall. There was a sitting area with a TV tastefully hidden from view in a teak armoire against a waist-high wall. The teak headboard of the bed rested against the other side of the wall, facing the courtyard with the sea-view to the left. The red marble bathroom featured an enormous white porcelain Jacuzzi for two. A window into the bedroom allowed the bather to look straight out through the bedroom windows out over the Gulf of Mannar. “It’s amazing,” I breathed. The porter installed the bag on the teak luggage stand, Dan gave him a tip, and then we were alone in the room.

After resting in the room for the afternoon we met Elaine at the bar of the big modern hotel across the street. We all got drunk on mojitos and discussed the worsening state of frustration and ineffectiveness that plagued her current project for a large international NGO. She explained that the problem was more on the level of the regional director as opposed to her native staff in Colombo. “I mean, after all, most of my staff is Muslim,” she explained, which I knew meant that her local staff were hard workers and weren’t at fault for problems with the project. I understood her comment the same way as if she had told me her staff was all-German I would have known they were on-time and precise. I realized that if she were trying to explain the situation to someone from America, someone who had never been to Sri Lanka, that person would not understand that Muslims are considered the most conscientious workers and it was a major bonus to have a majority Muslim native staff.

“Do you ever speak Tamil or Sinhala when you aren’t at work?” Dan asked her after our third round arrived.

“No, never.” She replied immediately. “I speak in English except when I am in the field. And to my three wheeler drivers,” she added.

“When I first learned Sinhala I used to speak to everyone, hotel staff, waiters, grocery store clerks” Dan replied, “because I wanted to practice. I wanted to reach out to people and charm people. But now, I only use it when I am interviewing for my project or with our drivers. No matter how well I speak the language I will always belong to another place. I will always have that ticket back to America and they don’t,” he finished as Elaine nodded in sympathy. I marveled at how completely the three of us understood each other and how effortlessly we could process the environment amongst ourselves. “Pretty soon we are going to be in a place where people don’t understand why it’s good to have a Muslim hotel owner,” I commented. “When we get back to America it’s not like anyone is going to understand how creepy it was to see young Sinhala men with Russian women falling all over them at the high-end hotel near Sigiriya,” I continued.

“Going back is tough,” Elaine confirmed.

“Not too many people really understand what you’ve been through,” Dan explained. “They think that it’s been like a really long vacation and maybe you’re homesick, but what you’ve gone through is so much bigger.”

“Right,” I replied. “And I’m not going back to where I came from,” I explained to Elaine. “Dan and I didn’t live together before moving to Sri Lanka, so I’m not going home to my old house and my old job. All my stuff is in Dan’s basement and I’m not going to work nights anymore. That was fine when I was single, but it’s tough when you are in a relationship.”

“It sounds like you have some transition ahead of you,” Elaine agreed as we finished our drinks.

When Elaine called her driver we walked her to the carport of the hotel. “You guys have been my support here,” she told us, “I’m really going to miss you.”

“You know,” I replied, “We’ve been saying goodbye to people for days. I had no idea we had so many friends here until it was time to leave.”

“It sneaks up on you,” she replied laughing as her driver pulled up. We hugged her goodbye before heading back across the street to our suite at the Galle Face. “I hope she isn’t here when we get back,” I remarked to Dan once we were back inside the Galle Face lobby. “Even though it would be great to see her again, I hope she has moved on to a better country, some place she can have more fulfilling work and be happier.”

“Everyone wants to leave,” Dan replied. “And I do think it would be good for Elaine to get out of here,” he agreed as the climbed the teak stairs to the Ocean Suite.

We spent the next day sleeping in and lounging by the pool. After watching the sunset from the Jacuzzi we enjoyed a final dinner at The 1864 restaurant with all of our favorites. After our final breakfast buffet on the terrace we packed the bag and loaded into the airport express van for the 30-minute trip to the airport. The driver took a shortcut through some of the most decrepit parts of the city. Even though it was depressing, Colombo had become familiar. Somehow going home to Charlottesville seemed like just as much of a leap as coming to Sri Lanka. “Remember how when we first met I was all nervous, wondering if you would ask me to come to Sri Lanka with you?” I asked Dan as our van sat in gridlock traffic next to a vacant lot that had become a local landfill.

“I bet you think that’s pretty funny now don’t you?” he joked.

“Yeah, I do,” I confirmed, smiling and taking his hand.

“Now do you understand why I said that before I met you I was seriously considering turning this grant down?” He asked.

“Yes, I get it now,” I replied. “I couldn’t have imagined it before, but I get it now. You’d have been so isolated without me.”

“It would have been terrible,” he agreed as the van started to move again. “Right now I just want to get home and start writing,” he finished, leaning his head on my shoulder.

Northern Tour

After returning home from Colombo, Dan went to his new field site, the temple run by the student of a heretical monk. My first evening in the annex alone was quiet until after dark when two bats flew in the open doors to the patio and got stuck in the bedroom. I turned off the lights in the living room then darted into the dark, bat-filled bedroom, and turn on the lights to motivate them to leave.

After securing the house and reading myself to sleep I had to get up and use the bathroom. When I turned around to flush I noticed the biggest spider I had ever seen on the wall of my bathroom. This spider was brown, fuzzy, and drastically larger than anything I had ever imagined in North America and anything I had ever seen on display at a science museum. Its leg-span was the size of a baseball and the lower abdomen was the size of a quarter. Worn out from dealing with the bats, I was simply too terrified to kill it. “How could my life in Sri Lanka be complete without encountering something that could kill me in my own bathroom?” I reasoned as I pulled the covers of the bed around me. I felt grateful that it hadn’t been a scorpion or a snake as I drifted off to sleep to dream about spiders for the rest of the night.

When I woke up the next morning, I postponed using the bathroom as long as possible. When I couldn’t stand it any longer I gingerly walked into the bathroom, carefully inspecting every surface as if as massive brown spider would be difficult to spot. I could detect no trace of the previous night’s visitor. The next day was Sunday, so I mounted a solo visit to the Botanical Gardens in the morning. Sri Lanka had lost to Australia in the Cricket World Cup the night before, so I felt a little nervous that someone might see my blond hair and think I was an Aussie, but I decided that everyone was probably too tired from staying up the night before to cause me any trouble. I was curious to see how the Sri Lankan public would treat their team. “Would they burn the players in effigy and attack their homes like in India?” I wondered, “Or would they murder their coach like in Pakistan?” As it turned out the returning team was given a hero’s welcome with full-page ads in the papers congratulating them and celebratory banners posted outside of stores thanking the multi-ethnic, multi-religious, team for representing Sri Lanka so well on the international stage.

My run in the Gardens went well. I brought my iPod velcroed into its shoulder strap to help me ignore everyone. If the pod of Muslim women was laughing at me or the gaggle of Sri Lankan young men were taunting me, I didn’t know as I ran in a zone of my favorite songs. After stopping at Food City on the way home, I realized that I only had fifteen more days in Sri Lanka. I knew that our last two would be spent at the Galle Face in Colombo, “so those don’t really count,” I told myself, “It’s more like 13, and when Dan gets back from his field site we are going to become tourists again.” After Dan’s last trip to gather data we were finally going to finish our Northern Tour of the World Heritage Site ancient cities.

We had started the Northern Tour in August, before even moving into the annex. The ISLE undergrad study-abroad program that had served as Dan’s first bridge to Sri Lanka in 1996 was in session and Dan wanted us to accompany them on the Northern Tour because a prominent archeologist from Peradeniya University led the students through the sites.

Approximately 100 kilometers north of Kandy, the first stop was Anuradhapura, the first capital of Sri Lanka in the fourth century BCE. The Cakravartin King Ashoka sent his son, the arahat Mahinda, accompanied by several monks on a diplomatic mission to Anuradhapura in the early third century BCE. The delegation was received by King Tissa, the grandson of the founder of the city, who took the 5 precepts of a Buddhist layman and became the first royal patron of Buddhism in Sri Lanka. Some archeological evidence at Anuradhapura suggests the presence of Buddhist and Jain monks prior to Mahinda’s arrival, but Tissa’s official patronage and support of the Buddhist community founded what would become one of the ancient world’s foremost bastions of Buddhist scholarship over the course of its 1200-plus years as a capital city and major trading center. Drawn by its monastic libraries, the monk Buddhagosa traveled from India to Anuradhapura in the fifth century CE to make the knowledge of the Sinhala monks available to the entire Buddhist world and wrote his “Path of Purification” commentary during his visit. Because of the easily traveled flat, dry landscape, not only monks made the trip to Anuradhapura. Frequent military invasions from the Indian mainland resulted in occasional Hindu rule such as the reign of the Tamil king Elara. Acknowledged by Pali chronicles as a good an just ruler, after a forty-year reign he was defeated in the early second century BCE by the Sinhala cultural hero Dutugemunu, whose name means “Gemunu the Vicious.” Anuradhapura was finally sacked and deserted in 1017 CE after an invasion by the Cholas from Southern India. The destruction to the crucial irrigation system of earthen tanks was so severe that the area was almost completely abandoned until British excavation of the ruins was followed by tank restoration and resettlement projects.

In our car hired from Malik, Dan and I had arrived before the ISLE students at the first site in the Anuradhapura area, Vessagiriya. When I stepped out of the car I saw a series of caves formed by three large, bulbous, outcropping of rock shoved together on a otherwise flat, featureless landscape. Dan explained that the cave complex is thought to have housed early Buddhist and Jain monks. “What were the Jains doing way down here and why did they die out?” I asked.

“Probably because Buddhism eventually received the royal patronage,” Dan answered, “but who really knows,” he finished as we walked toward the first cave formed by two of the large boulders overlapping. Dan then showed me how the first thing the monks did was carve a drip-ledge into the rock above the opening to the shallow cave so that rainwater would run off to the side and not into the cave. We then ascended the footholds cut into the boulder to the top of the pile of gigantic rocks and crossed the structure to the other side. Under a ledge three beds had been carved into the rock. The rock inside the demarcated area of the bed was polished into a smooth undulating profile to suit the contours of a human spine. “First a drip ledge, and now this,” I remarked. “How far away are they from ‘High and luxurious beds?’” I asked sarcastically, referencing the eighth precept taken by Buddhist monks.

“Yes, this is the origin of the corruption of the Sangha right here,” Dan joked back as he turned to look at in inscription under the drip ledge. I studied the beds, realizing that I was seeing something incredibly ancient, a humble modification to the landscape made and used by ascetics who were practically contemporary to the Buddha in the grand scheme of history. “How old are these things?” I asked.

“Probably fourth or fifth century before Christ,” Dan answered without turning around.

“What are you looking at?” I asked.

“These symbols,” he said excitedly, moving to the side and pointing, “These look like Brahmi characters.”

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Brahmi is an ancient script from which all South Asian writing systems derive,” Dan explained. “This character would indicate that this site is very old, fifth century before Christ or so.” I peered at the character that looked like a backwards “K.”

“That’s the short ‘a’ sound,” Dan explained, “These inscriptions are the names of the donors who funded the monks to live at this site,” he continued as the ISLE bus pulled up.

I sat with the ISLE students and listened to the professor give a background of the site and point out the drip ledges while Dan’s old friend Herath, the Sinhala teacher, dragged Dan back down the hill to chat in Sinhala. I followed the group around the site like the kid nobody wanted to talk to while Dan and Herath caught up. The ISLE program had just gotten underway and the study abroad undergrads were just getting to know each other and forming their own preliminary cliques. I didn’t really factor into the equation for them. For some reason I didn’t feel like I could just walk up to a group of the girls and say “hey, how do you like Kandy so far?” since I had just gotten there myself and was pretty miserable. I trailed behind the little herds as they explored the beds cut into the rock and Dan showed the Brahmi character to Herath and they both seemed very excited about it, jabbering in Sinhala. “This is going to suck,” I realized gloomily.

Over the next three days we slogged through the heat of the Sri Lankan plains to visit the ruins of the Anuradhapura area, crisscrossing the dirty, modern resettlement city situated on the outskirts of the ruins. We saw various Buddhist and royal gardens, tanks, bathing ponds, as well as stupas all in varying states of restoration. I listened to the lectures and walked around silently with the ISLE students, like ghost. By the third day the sheer scope of the Anuradhapura amazed me. “This place is massive,” I commented to Dan as we pulled up in our car behind the ISLE bus at the largest stupa in the world, the Jetavanaramaya, “And this stupa is huge!” I exclaimed when I saw the 400-foot, slightly lumpy, oval mound of bricks. Elaborate scaffolding for restoration jutted from one side of the stupa for new bricks to be brought to the top in small bushels and placed into the uneven side of the stupa by hand.

“It is the third largest structure in the ancient world,” Dan replied, “Right behind the Great Pyramids of Khufu and Khafre at Giza.”

“No shit,” I replied in awe as we walked towards its massive base.

“It is one of the eight pilgrimage sites here in Anuradhapura,” he continued. “The Anuradhapura pilgrimage circuit is called the Atamasthana. It consists of the Bodhi Tree, six stupas all built over relics of the Buddha, and the Lovamahapaya, the Brazen Palace. That was a large structure with a bronze roof, that’s where you get the name ‘Brazen Palace,” but wasn’t really a palace but a temple,” he explained as we began to walk along the base of the Jetavanaramaya.

“Why do people go on pilgrimages to these places?” I asked.

“For Buddhism to exist you need Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha right?” Dan asked rhetorically. “The Buddha is represented on earth by his relics, the Dharma by the texts and monks who have memorized the texts, and the Sangha is the community of monks and lay people. In the Sutras the Buddha tells his followers that pilgrims will go to heaven if they visit the places of his birth, enlightenment, first sermon, and death. Those places are way up in Nepal and Northern India, so a local tradition of pilgrimages started, it’s a form of transferred spiritual mapping.”

“But part of a pilgrimage is to leave home,” I countered, “How was it a place of pilgrimage for the people of ancient Anuradhapura to go across town?” I asked as we continued circumambulating the huge stupa.

“The pilgrimage tradition for these eight locations didn’t start until after Anuradhapura was abandoned,” Dan explained. “When Anuradhapura was a capital city all of these stupas were part of huge monastic complexes, you couldn’t just have lay people showing up there all the time. Plus you don’t have the sense of leaving home,” he added. “The Atamasthana circuit is today part of a larger circuit called the Solosmasthana,” he continued. “The chronicles of Sri Lanka record that the Buddha made three trips to Sri Lanka and visited a total of eight places all over the island. For the people of Anuradhapura, the places where the Buddha visited were the places of pilgrimage. Then after the fall of Anuradhapura, the eight places where the Buddha visited plus the eight sites here make up the Solosmasthana,” he finished. I realized that we had been walking for a while and we hadn’t even made it to the back of the Jetavanaramaya.

Dan drifted back to talk to Herath near the scaffolding while I continued around the back of the huge stupa. The flagstone terrace around the base of stupa was very uneven and I had to walk slowly and carefully. An all-male work crew toiled in the blazing sun moving bricks from their delivery site in the parking lot to the base of the scaffolding and into buckets to be hoisted up to the area of repair at the top of the stupa. Women worked in smaller groups re-fitting the large paving stones to repair the uneven terrace. As I worked my way along the base of the stupa, I remembered my trip to South India. While touring temples in Tamil Nadu, I realized that many of the temples marked the locations of important acts of the gods and goddess. I was stuck by the Hindu worshipper’s incredibly strong sense of connection to the divine through geography as my guide explained that goddess Parvatti had done her penance on that very spot. “Relics make sacred geography portable,” I reasoned, squinting to look up the bulging side of the brick stupa. “Back home is almost totally devoid of spiritual geography,” I thought as I moved into the shade of the stupa, “Unless you want to pilgrimage to the Morton Thrifty Food to see the image of the Virgin Mary spontaneously formed from a drip in the ceiling of a case in the frozen food section,” I ruminated. I paused to rest in the shade of the stupa and tried to feel like a Buddhist pilgrim, like I was somehow closer to the divine standing next to the gargantuan structure. When I was unable to feel inspired I headed back to the car.

In contrast to the construction-zone Jetavanaramaya, the Bodhi Tree at Anuradhapura was a living Buddhist site. After Ashoka’s son Mahinda came to Sri Lanka with an entourage of monks, his sister came along as well, bringing a cutting from the Bodhi tree under which the Buddha The cutting was planted in Anuradhapura and is the oldest continually tended tree in the world with monastic records dating back to it’s planting in 288 BCE. Cuttings from the Anuradhapura Bodhi tree have been transplanted to Buddhist temples all over the world.

On May 14th, 1985 two busloads of LTTE soldiers attacked pilgrims spending the poya or full-moon day observing the precepts under the sacred Bodhi tree, killing 120 pilgrims. The result was a heavily fortified Bodhi tree complex. We were all patted-down twice before entering the sandy area around the 6.5-meter high terrace forming as a large planter for the sacred tree. “That tree is doing pretty well for a 2,300 year old tree,” I remarked to Dan once we entered the enclosure on the evening of the third day of the tour.

“That’s a newer tree,” he explained, “They planted it to shade the real tree. The real tree is just a little thing, see there, supported by the gold crutches,” he said pointing up and under the lush Bodhi tree to a little gnarled branch growing out of the ground as we walked up the first set up steps to the first terrace.

“Ok, that makes sense,” I conceded, looking at the listing little tree. We stood on a lower terrace with the Bodhi trees planted in another terrace just above our head craning our heads to see the little Bodhi tree. “For the Army’s flag-blessing ceremony they take the flag of each regiment and go all the way up and place them around the original tree itself,” Dan explained as we walked around the inner terrace. “Some people feel that this tree is the closest thing on earth to a living Buddha.” he remarked as we watched the pilgrims dressed in white praying and offering flowers.

“South Asians love trees,” I remarked. “That’s what I’ve learned in my travels.”

“That’s the wall the LTTE drove the bus through on poya day for the 1985 massacre,” Dan pointed to the wall of the sandy enclosure as we rounded another corner of the terrace. “One of the monks I’ve interviewed a few times up here was a little monk at the monastic college nearby,” he continued. “When the massacre happened he and a few of the other monks snuck out of their dorms to go and see the bodies.”

“No kidding,” I replied, imagining what a mess the whole place must have been as we completed our circumambulation back to the place where the pilgrims reverently prayed. I noticed that the Peradeniya professor and his family were among the Sri Lankans placing flowers.

By day four, I could hardly believe that we were at another monastery ruin, “This place must have been totally over-run by monks,” I thought, envisioning saffron robes swarming over the sprawling complex of ancient building foundations and piles of rubble.

“One of the interesting things is that there were orders of Theravada as well we Mahayana monks practicing here,” Dan commented, “there were three main fraternities, The Mahavihara was the more conservative, Theravada group, the Abhayagiri Vihara was more Mahayana, and the Jetavana Vihara, which was actually a part of the Abhayagiri.”

“But only Theravada survives today right?” I asked.

“Yes,” Dan acknowledged. “Mahayana Buddhism started to develop in the first century of the Common Era. Both schools were represented here throughout the occupation of Anuradhapura, but when the city was sacked and the capital was moved to Polonnaruva the king consolidated the monastic fraternities and began the tradition of writing laws for the Sangha. The kings continued writing laws for the Sangha until the fall of the Kandyan kingdom to the British,” he finished as we walked around the exposed foundations of the ancient monastery.

“The thing about Anuradhapura is that the stuff here is really old, especially for a Buddhist site” Dan remarked. It’s much older than the stuff you see in Thailand for example.”

“I guess that’s true,” I remarked thoughtfully, “I never really thought about it, but Bagan in Burma and Angkor in Cambodia were all started after Anuradhapura was already sacked. That’s pretty remarkable, I mean, it’s no Great Pyramid at Giza, but this stuff is old,” I teased, raising my left eyebrow.

“Oh I see,” Dan replied laughing, “Anuradhapura isn’t old enough to impress me Dan, I’ve been to the Pyramids at Giza,” he said in his high-pitched “mocking Sara” voice.

“Really though, my favorite thing is still those beds cut into the rock,” I commented. “I know it’s simple, but I’ve never seen anything like that, an ancient bed cut into the rock of a cave. I keep thinking about the monks who lived at that site. They must have been really excited and thinking that they were doing something brand-new.”

“It’s true,” he replied, “The ideas behind asceticism hadn’t really been around all that long before the time of the Buddha,” he finished as we headed back to the car.

Not all of the stupas at Anuradhapura were under heavy construction or in advanced states of disrepair. The second largest stupa, the Ruwanvelisaya, had been fully restored and now functioned as an active place of worship and focal point for a monastic residence. After Dutugemunu defeated Elara he built the enormous stupa partially out of guilt for killing so many people. When the British first encountered the Ruwanvelisaya, it was completely covered in soil and plants like an abrupt little hillock on the flat landscape. The stupa was excavated, the dome re-shaped, and the whole thing re-plastered smooth so that it looked like half of a huge boiled egg jutting out of the ground with a box crowned by a steeple on top. While circumambulating the stupa at the end of the fourth and final day, I watched the monks tie a long ribbon of stitched together monastic robes around its massive base. I caught up to Dan to ask him about the practice. “The stupa houses a relic,” he explained, “And the relic represents the Buddha, so tying the robes around the stupa symbolizes the idea that the monks robes and integrity of their lineage ties them back to the Buddha himself. That’s one of the reasons that maintaining the lineage is so important,” he added as we watched the monks roll the huge ball of robes around the lower lip of the stupa.

The ISLE Northern Tour continued on to Polonnaruva, the more southern and eastern Medieval capital established after the fall of Anuradhapura, but we returned to Kandy to settle into our new home and vowed to finished the Northern Tour on our own. Now, twelve days before departing from Sri Lanka, it was time to resume our Northern Tour starting with Polonnaruva. In 1070, the Sinhala King Vijayabahu drove the Cholas back to India, fifty-three years after the 1017 fall of Anuradhapura. Polonnaruva preserved as a royal capital until 1284 when the city fell to the Pandyas, who had replaced the Cholas as the dominant power in South India. The Sri Lankan capital was then established farther south at Dambadeniya, ushering in an era of smaller kingdoms scattered across the island, shifting centers of power. The Dambadeniya period marked the end of the great architectural age began a era of focus on the production of Sinhala Buddhists. The regal symbol of power, the tooth relic, was transferred from place to place before it wound its way to the Kandyian kingdom. Kandy was not a prominent or powerful kingdom and became the home of the tooth relic simply because it’s jungle location made it the last kingdom to fall to the British.

Since Polonnaruva functioned as a royal capital for a much shorter period of time, the ancient ruins were restricted to a smaller, more manageable area. It was also not recognized as a place of pilgrimage for contemporary Buddhists. The archeological sites were handily concentrated into a much smaller area easily manageable in a two-day period. Our first stop was the Gal Vihara, featuring four large Buddha statues all carved directly into one large slab of granite. I grudgingly removed my shoes at the security guard’s booth before walking into the sandy area in front of the images. “I feel like a beggar walking around Sri Lanka barefoot,” I thought unhappily as I sidestepped a pile of dog feces. I remembered the humiliation of walking barefoot through the parking lot of the Temple of the Tooth in Kandy through dirty motor oil and muddy puddles. “This is to humble me in front of the image of the Buddha,” I suddenly realized as I followed Dan to the first statue in the series, a larger-than life seated Buddha in the Samadhi mudra with his hands folded in his lap. To reach the statue we had to step over the low foundation of the destroyed image house that used to surround the statue. Each statue had previously been enclosed by it’s own small structure. Standing barefoot in front of the Samadhi image in the sand, trash, and ants it struck me that walking barefoot in the presence of a Buddha image not only humbles the worshipper, but also makes one walk barefoot as the Buddha walked barefoot from the time he left his father’s house to seek enlightenment. “So it not only makes you a beggar at the Buddha’s feet,” I reasoned as I followed Dan over the low foundation around the Samadhi image and up onto the higher foundation for the next image, “But it also makes you take on a quality of the Buddha.”

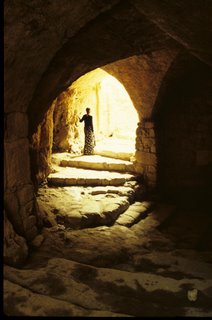

The next image was a life-sized rendering of the seated Buddha teaching the Abhidharma to his mother and the gods in heaven carved into the back of a man-made cave into the rock. Next to the cave and still within the same enclosure, a lengthy inscription detailed the king’s rules for the monks. “People go barefoot in Hindu temples too,” I reminded myself as I peered at the seated statue, “So the barefoot thing is probably part of that tradition too.”

Continuing down to the left we stepped into the next foundation surrounding a seven-meter Buddha standing with his arms crossed across his chest. “You see that mudra painted on the ceiling at Dambulla,” Dan explained, “In the mural the Buddha takes that mudra after he attains enlightenment and stands up to look back at the Bodhi tree under which he had reached his realization.”

“It’s like he’s saying ‘Ok, my work here is done,” I commented as we stepped across the foundation into the next image house that once sheltered the fourteen-meter-long reclining Buddha entering Parinirvana or final extinction. The swirling grey, black marbleized grain of the granite flowed beautifully down the statue. The Buddha’s head rested on the traditional round bolster pillow with the sun-wheel symbol on its end. The pillow was executed with a depression under the Buddha’s hand supporting his head on the pillow, giving the rock a soft, comfortable appearance.

The standing and reclining Buddha were difficult to take in at close range, so Dan and I stepped out of the enclosure, across the sand, and scampered up a large sloping rock facing the four statues. “I like being able to see them all at once,” I remarked, “but judging by the foundations, the structures built around them must have been very small and cramped.”

“That’s the way it would be in a traditional cave temple,” Dan replied, “a big Buddha statue in a small space.”

“I guess it’s meant to overwhelm you,” I added, nodding. We studied the statues in silence before returning our feet to the safety of our shoes and continuing on to the various other ruins.

After two days at Polonnaruva touring the remnants of palaces, stupas, and monasteries, we traveled back down towards Kandy and back in time towards Dambulla, a monastic complex of more than 80 caves initially inhabited in the third century BCE. Somewhat on the way we stopped at Aukana to see the twelve-meter-tall standing Buddha cut directly into the rock facing the earthen wall of the large tank that supplies Anuradhapura with its water. The statue was built in the fifth century, during the middle of the Anuradhapura period. The statue faced an ancient but nearly dead Bodhi tree with a shrine around the base of the tree. “It’s going to be embarrassing when that tree is completely dead,” I remarked to Dan, scrutinizing the tree. Only half of the branches had leaves and the few leaves that clung to the lower branches had turned yellow and were falling to the ground. Standing under the dying Bodhi tree with its yellow leaves strewn over the ground felt like fall to me, but then I had to remind myself that in Sri Lanka there was no such thing as fall.

The statue and withering Bodhi tree belonged to a small, rural monastery. The younger student monk sold us our two-dollar tickets, handling the money directly while the older monk chased us down with his donation book in his hand as we admired the statue. When the monk approached Dan did not bow and did not address the monk in Sinhala. “I thought you bowed to the robes and not to the monk,” I remarked when the old monk realized that these Westerners weren’t good for any money and wandered off.

“I just can’t believe that he approached us with donation book in hand,” Dan replied unhappily.

“He just sees you as a rich Westerner he can mine for money for the Sunday school he is building, and that’s dehumanizing,” I remarked.

“Yeah, and you have to think, what’s the purpose of the Sunday school?” Dan asked me directly. I shook my head to indicate that I had no idea.

“So parents will send their kids to Sunday school and give even more money,” he answered himself. “It’s a business,” he continued, “And this is why monks should not own the temples. I know there is a really long tradition of it here in Sri Lanka, but as soon as they start doing stuff like fundraising and handling money they are pretty far from what monks should be.”

“And if you were to bow to him and address him with the proper Sinhala words to show respect for a monk and he continued to treat you as a cash-machine then I can see how that would be really humiliating,” I agreed.

“The Buddha said that some of the rules for monks would have to change,” Dan admitted, “But he didn’t say which ones, that’s the problem. But greeting people with your donation book and having your little monk selling tickets seems like it’s pretty far from the original intention,” Dan finished sadly.

“The monks own the temples here,” I added, “They have their own political party and are elected to office, its crazy how much power they have.”

“Not only are they elected to Parliament themselves,” Dan replied, “But they also get paid or gifted for endorsing certain candidates for office, the current president gave the heads of the biggest monastic fraternities expensive cars for endorsing him, but the monks won’t accept them until he agreed to pay the insurance also,” he explained.

“That’s crazy,” I replied, pausing. “What is that mudra anyway?” I asked, referring to the position of the Buddha’s hands. His left hand reached back up to his shoulder as if the statue had to hold on his robes draped over the left shoulder. His right hand pointed up to the sky with his palm perpendicular to the plane of his face. “Is that the famous ‘holding up my robes on the bus’ mudra?” I joked.

“I think it’s the vitarka plus the abhaya mudras” Dan replied. “You see a bunch of the statues in the caves at Dambulla in that posture, it represents blessing,” he explained as we headed back to the van.

After lunch we visited the Dambulla caves. The murals and statues depicting the Buddha and his life events were spread over five lower caves and were initiated in the first century BCE with major renovations in the 11th, 12th, and 18th centuries. In 103 BCE, just thirty-four years after Dutugemunu death, Anuradhapura was lost again to South Indian invasion. The king of Anuradhapura, Valagamba, was defeated by Indian invaders and fled south to Dambulla, where the monks meditating in the caves sheltered him for fourteen years. When he regained the throne of Anuradhapura in 89 BCE, he rewarded the monks by funding the construction of the large cave-temple complex. At the time of our arrival Dambulla currently functioned as an active monastery boasting its own lineage and ordination platform since the late eighties.

After the short, steep, 150 meter hike up the side of the hill in the blazing noon sun, we stepped up into the white, columned façade running under the original drip-ledge entrances to the five painted caves. When we entered the first cave into the cool air I felt a rush of relief from the heat. The first cave was small and utterly dominated by a garishly painted reclining Buddha similar in size to the reclining Buddha at the Gal Vihara at Polonnaruva. Squeezed between the statue and the wall of the cave I realized the claustrophobic the intimacy with which the original devotes at Gal Vihara had experienced that statue. As if reading my thoughts, Dan remarked rhetorically, “I wonder if those Buddhas at the Gal Vihara were painted.” I had no answer for his question and instead reflected that we had both instinctively moved away from the large statues and were more comfortable relating to them from a far, as an overview.

The other caves were a riot of murals and statues crammed into small spaces, including scores of standing Buddhas in the vitarka, “holding up my robes on the bus,” mudra.. Dan and I craned our necks to pick out various stories of the Buddha’s past life and events of his life as Gautama Buddha on the ceiling of the largest cave. Dan pointed out the depiction of the Buddha standing with his arms crossed looking back at the Bodhi tree under which he attained enlightenment. “So we know what that mudra means, at least to the people who painted this mural and probably to the builders at Polonnaruva too,” he reasoned. I snapped a picture. “That’s some fancy scholarship at work,” I praised him as we left the cave.

After Dambulla we headed to our hotel to rest up for the next day when I would tackle Sigiriya, the rock fortress I had seen in a book long before meeting Dan. Since Dan’s knee was bothering him I planned to do the climb alone. A bout of food poisoning kept me awake all night, ruining the early start I had planned. I had to wait until 10:00 before I was able to eat something and keep it from spewing out one end or the other. I started out alone with the driver of the van for the 30 minute drive to the base of the 370 meter magma plug left behind from the erosion of a prehistoric volcanic cone first inhabited by Buddhist monks in the third century BCE. During the reign of King Kasyapa from 477 – 495 CE it was converted to a palace with the addition of the famous frescos, Lion’s Gate, moats and gardens. According to the Mahavamsa, or “Great Chronicle,” King Kasyapa was the son of a King of Anuradhapura, King Dhatusena. Kasyapa murdered his father by walling him alive and usurped the throne that rightfully belonged to his brother Mogallana, who then fled to India. Knowing that Mogallana would eventually return, Kasyapa is said to have built his palace on the summit of Sigiriya as a fortress and pleasure palace. As predicted, Mogallana raised an army in India, returned, and declared war. During the battle Kasyapa's armies abandoned him and he committed suicide by falling on his sword. After King Kasyapa’s tenure, the fortress was re-converted to a monastery and utilized until its abandonment in the 14th century in conjunction with the general decline of Buddhism on the island during this period. It was re-discovered and excavated by the British.

By 11 AM I stood at the base of the magma plug, squinting up at it in the hazy late morning sun. After a few initial touts at the entrance to the gardens, I was generally left alone by the herds of Sinhala boys that roamed the gardens. Dan and I paid 40 dollars for admission to Polonnaruva and Sigiriya, but the locals got in free. With a cold liter of water in my small backpack I made my way to the base of the huge rock and started up the steps. I then ascended a metal spiral staircase bolted into the side of the rock to reach the cave of the frescos about halfway up the rock face. The buxom female frescoes of Sigiriya are the Mona Lisa of Sri Lanka. Their images are reproduced everywhere from advertisements, to hotel rooms, to the 2,000 Rupee note. When I saw the Mona Lisa in the Louvre I was stunned by how small it was. Likewise, when I reached the little cave originally embellished with 22 frescoes, each smaller than life, I was surprised at the detail worked into each little image. Each image was a woman painted from her slender waist up. Each woman was extraordinarily unique, as if patterned on a living model. Some had pale skin-tones, some had rich chocolate skin-tones, and a few even exhibited a greenish glow that somehow managed to look elegant and beautiful. All of the images were depicted as topless except for one, and all were adorned in spectacular jewelry and headdresses. Most of the women held fruit or flowers in their hands. I remained for a while in the little niche in the side of the magma plug, studying and photographing each image. Once I was alone with the security guard he invited me over the railing to a further reach of the cave to see six more images and pointed out various faint re-drawings of faded hands and nipples. When I heard the next gaggle of boys approaching I gave the guard twenty Rupees for the extra tour and continued back down the spiral staircase to the regular ascent up the side of the rock.

“This is the last crumbly old thing you have to see for a long, long time,” I reminded myself as I tackled a set of stairs cut into the rock leading to the penultimate landing. When I reached the landing there was a sign next to a pile of sandbags that read in Sinhala, Tamil, and English “Please in view of restoration efforts each person to carry one bag of sand or bricks to the top.” I noticed five workmen in lunghis resting in a corrugated tin hut as the tourists toted the canvas bags of sand up the final ascent of metal stairs bolted to the rock. I picked up a bag of sand and headed through the huge lions paws that once served as the base of a massive statue marking the entrance to the flat top of the magma plug.

Once I reached the top and handed off my sand to the laborer I walked around the perimeter of the roof of Sigiriya, admiring the view from all directions. High up on the rock, the jungle, white stupas, and the occasional gigantic standing Buddha statues dotting the surrounding landscape once again seemed lush and exotic. I felt amazed that my life had led me to this peak on this distant island off the tip of India.

When the heat of the day and lack of shade started to burn away my wonder, and I started back down the metal stairs, through the lion’s paws, and down the stairs cut into the rock. Halfway down the stairs I recognized Yuko, the Japanese woman from the Goenka meditation course at Dhamma Kuta. I greeted her and we talked for a few minutes about the things she had seen and the things I had seen since Dhamma Kuta. I didn’t want to return to the summit with her, I told her, so we said good-bye after a few minutes. I mused the oddity of the coincidence for the remainder of my decent. “I guess there is a limited number of places tourists on this rock go,” I reminded myself, “But still, it was a pretty amazing coincidence.

Back in the car park I located the van and then my driver for the trip back to the hotel. Driving to Sigiriya I had paid close attention to the route since I was traveling alone, even though Dan had used this driver two other times, we had been using him for four days, and he worked for Malik. The only drivers I was comfortable with were Manju and his brother Kapilla. “If he is going to drive me off in the woods and kill me, I at least want some lead time,” I thought to myself as I internalized landmarks and signs. On the way home when we were supposed to fork left the driver forked right I felt my pulse quicken in my chest. We had turned off the blacktop main road lined with houses and shops onto a red dirt road stretching straight out into the rice paddies. “Maybe this is a shortcut,” I re-assured myself, taking a drink of hot water from the bottle in my small backpack.

“I don’t think this is the way we came,“ I remarked to the driver as we passed over one small bridge and then another, going farther and farther away from the main road.

“I think you are just nervous,” he replied dismissively and continued driving. I had already tried to call Dan when I had completed my descent, so I knew his phone was dead or out of range, but I pulled my phone out of my backpack to check his number again or perhaps call Malik. As I stared at the empty space where the signal bars should have been I could hear my pulse pounding in my ears as I realized that I was totally cut-off.

As we continued along the red dirt road it struck me ironically how much the red clay looked like the Virginia red clay around Charlottesville back home. “But we sure aren’t in Central Virginia anymore,” I reminded myself ruefully as I started to assess my available weapons. I decided that the moment the driver started to slow down and turn off the road I would choke him with the chord of my headphones. I had been sitting behind the empty passenger’s seat so I slid over to behind the drivers seat to get into position and pulled my headphones off of my iPod in my backpack. I was mentally rehearsing swiftly bringing the cord over and down when a man on a bicycle appeared. As the van began to slow I decided that I would take no action if it seemed that the driver was asking for directions. I felt reassured as the driver rolled down his window and gestured for the driver to approach. I could tell from the man of the bicycle’s gestures that he was indicating for the driver to turn around and return to the main junction. The driver looked back at me in surprise and turned the van around. “I will never forget this day,” he remarked in amazement as we went back to the junction. “I won’t either,” I thought to myself. “I have a very good sense of direction,” I explained coolly as we proceeded back to the main road to the bridge I remembered, passed the house I remembered, and correctly negotiated the next junction. Back at the hotel we collected Dan and the luggage and continued back to Kandy.